The Man Who Drew Music: Inside Harold Sakuishi’s Timeless Manga

There are some artists who don’t just tell stories — they tune them, like instruments. Harold Sakuishi is one of them. His manga doesn’t demand attention; it drifts toward you, quietly, until you realize you’ve been living alongside his characters for hours. Whether it’s the trembling pulse of a guitar in BECK: Mongolian Chop Squad or the quiet ache of 7 Shakespeare, his stories carry that rare sense of reality — the kind that feels unpolished, unpredictable, and alive.

I’ve always thought Sakuishi writes like someone who understands the small violences of growing up — the failures, the awkward dreams, the endless waiting that shapes a young artist’s life. His panels breathe like moments caught between boredom and beauty. Maybe that’s why reading his work doesn’t feel like following a plot; it feels like being there — inside the sound of a band practicing in a dusty garage, or within the mind of a writer looking for words big enough to contain a world.

Sakuishi’s stories aren’t just about art — they are art about living. His characters stumble, get up, laugh, vanish. But in each of them, there’s something distinctly human — a refusal to give up the noise of hope, no matter how faint it gets.

Manga Worth Reading: The World of Harold Sakuishi

Beck: Where Beauty Learns to Live Beside the Dirt

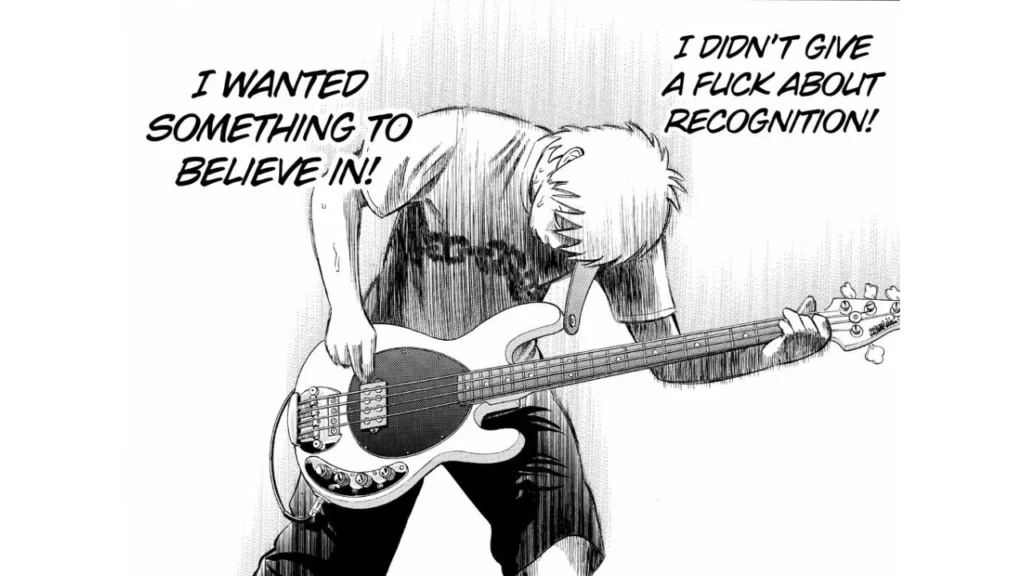

You and I — we mainly know Sakuishi-sensei through Beck. So first, let’s get through Beck first! It’s strange how a manga about a band can end up being about everything else — about life, redemption, and the quiet dignity of what’s imperfect. The central theme, I’ve come to believe, is the harmony between the shabby and the sacred. Between the dirty, the broken, the shadowed things — and the beauty that insists on blooming beside them.

Sakuishi doesn’t separate the two. He paints both with the same brush — one dipped in sweat, the other in sunlight. He doesn’t flinch from the dog feces on the sidewalk, the makeshift toilets at outdoor concerts, or the trash scattered after a show. These aren’t there for shock. They’re there to remind us that music, like life, is born from what’s left behind. Even the band’s breakout album cover — an image of that same trash — feels like an anthem to imperfection, a celebration of what the world tries to discard.

That’s what Beck is, really: the art of picking up what’s been thrown away. When they repair the broken SG, when Koyuki reshapes Eddie’s unfinished phrase into a song, when a tired middle-aged man like Saitou finds love — every act echoes the same truth. Sakuishi’s world doesn’t ignore the shabby. It redeems it. He keeps saying, quietly but firmly, that nothing is beyond repair if someone cares enough to hold it again.

Even Leon Sykes — the man soaked in sin and desire — becomes part of that redemption. Near the end, his reconciliation with Koyuki feels almost spiritual. He begins as the embodiment of everything corrupted, but deep down, he still believes in the raw, cleansing power of music. When Koyuki plays Devil’s Way for him, it isn’t victory — it’s grace. Sykes listens, and something within him yields. The next morning, he gives Koyuki Beck’s collar and tells the story of its origin — three dying dogs, two revived, one lost. Life and death, ruin and resurrection. It’s a quiet metaphor for everything Beck stands for: the world breaks, we pick up the pieces, and somehow, it sings again.

And maybe that’s why the story’s “fathers” — the men like Sykes and Ran — can’t be defeated by force. They only fall away when faced with understanding, when their pain is recognized and gently carried upward. In Sakuishi’s world, wisdom isn’t loud. It’s patient. It knows that redemption demands empathy, not defiance. Even victory is tender. If you want stories that speak life and music in one series like BECK, check out our article on the best anime manga about music.

7 Shakespeare: The Man Behind the Curtain

While I was writing about Beck, I found myself thinking — what else has Harold Sakuishi hidden under his sleeve? It’s funny how one story opens the door to another, how curiosity becomes a small rhythm that keeps you turning pages. That’s when I discovered 7 Shakespeare.

Everyone knows Shakespeare — or at least thinks they do. Romeo and Juliet, Hamlet, Macbeth — he’s the man credited with inventing almost every story pattern we still live by. But behind those words, there’s a shadow. We don’t really know who he was, or what he carried inside him. And that’s where Sakuishi steps in. 7 Shakespeare is his answer to that silence — a historical what-if, a reimagining of the man behind the myth.

I’ll admit, when I first finished it, I thought the ending came a little too suddenly. It felt like someone had stopped the music mid-note. But then I learned the truth — the series had switched publishers midway, and the continuation lived elsewhere. Once you know that, you realize it’s not an abrupt ending, just a pause — a breath before the next act. The story itself, though, unfolds from an angle I never could have imagined. It doesn’t feel like a dry historical drama. It feels like a whisper from another time — like Sakuishi reached across centuries to touch the restless pulse of a writer who, in his own way, was also a musician of words.

Of course, it isn’t a manga for everyone. Sakuishi’s art here feels even more idiosyncratic — sharp lines, unusual faces, expressions that linger too long on the edge of discomfort. It’s beautiful in a raw, unpolished way, but I can imagine some readers stepping back. And then there’s the theme itself — not everyone wants to dive into Elizabethan London or the culture of that era. But if you do, if you have the patience to listen, you’ll find that same Sakuishi heartbeat beneath it — his fascination with how art and survival intertwine. You can tell he loves history the way he loves music — not as something distant, but as something alive.

What I admire most is how he recreates the feeling of a world in motion — merchants and playwrights, dreams and debts, everything steeped in the smell of rain and wood and ink. You can feel the rhythm of his research — as if he read Romance of the Three Kingdoms and Western chronicles side by side, pulling from both to sketch something new. It’s a story for those who enjoy the weight of time, for readers who like to pause between lines and imagine the dust of another century settling in.

So maybe 7 Shakespeare isn’t meant for everyone. Maybe it doesn’t want to be. But for those who step inside, it rewards you quietly — with its intelligence, its audacity, and that same Sakuishi tenderness for the flawed and the forgotten. It’s a love letter to the act of creation itself, told by a man who understands that art, whether through music or words, is always born from the mess of living.

RiN: The Fire That Follows Stillness

After Beck, I thought I had seen everything Harold Sakuishi had to offer — the rhythm of youth, the sound of dreams, the beauty in the grime. But then came RiN, and I realized he wasn’t finished growing. Maybe that’s what makes Sakuishi-sensei so rare: he keeps evolving, even when he could have safely repeated himself.

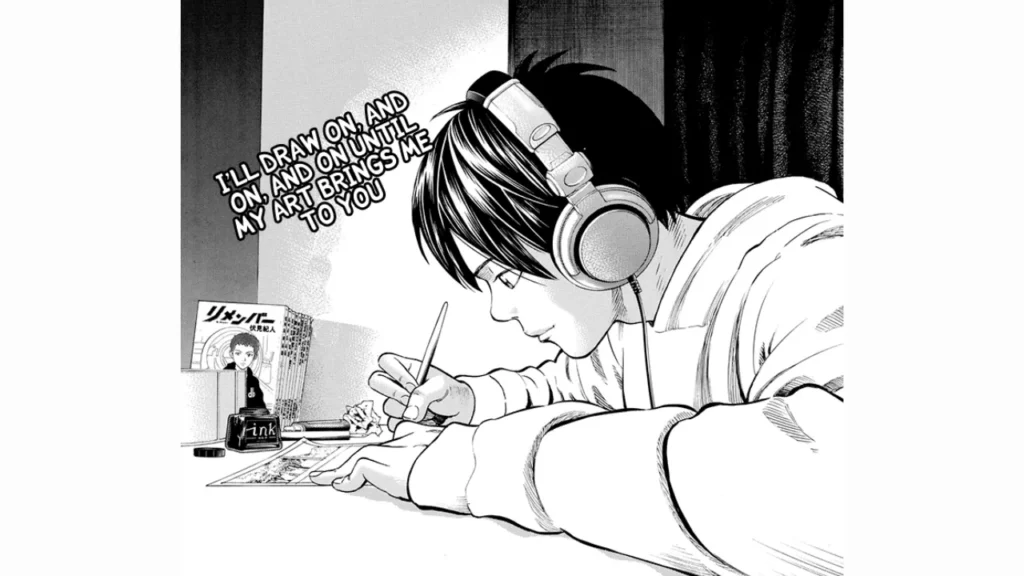

RiN begins quietly. Norito Fushimi is a boy whose school life moves like a long yawn — colorless, repetitive, half-asleep. But he dreams of becoming a manga artist, and one summer he gathers his courage, brings his best work to his favorite magazine, “Taurus,” and faces the inevitable: rejection. It’s the kind of moment we’ve all lived through in one form or another — that heavy silence between hope and humiliation. But what makes RiN special is what comes after. Fushimi doesn’t give up. He redraws, rewrites, and learns to love the ache of effort. And then, into his quiet persistence, enters Rin Ishido — a girl who seems to exist between this world and another, carrying something mysterious, maybe even divine.

Their meeting feels like a spark landing on dry paper. What unfolds is not just a story about manga, but about the act of believing in creation itself. And that’s where Sakuishi, the man behind the curtain, reveals himself most clearly. Because drawing a story about manga artists is never just “work” — it’s a confession. Every brushstroke feels like a small piece of autobiography, like he’s letting us see what it means to live a life where art and existence blur. You can sense his own struggles — the rejection, the stubborn love, the absurd joy of chasing something impossible.

The structure, at first glance, feels familiar — like Beck all over again. The slow rhythm of daily life, the steady rise of a dream, the gathering of small moments that suddenly start to mean everything. But RiN moves deeper into the strange and spiritual. It dares to reach for something more mysterious — the way art touches what logic cannot. The occult thread that runs through Rin’s character doesn’t feel gimmicky; it feels like a metaphor — the invisible hand that guides those who create, the divine accident of inspiration.

Sakuishi’s art, as always, carries his personality — sharp, lively, occasionally awkward, but full of sincerity. His characters don’t just look passionate; they feel passionate. Their faces sweat, their hands tremble, their words spill out like something urgent that refuses to be held back. There’s a particular scene where Fushimi shouts, “Manga is all I have!” — and you believe him. You can hear Sakuishi himself somewhere inside that line, quietly agreeing.

Reading RiN left me in a strange state — dazed first, then restless. That familiar post-Sakuishi feeling where your heart starts to hum, and you want to pick up something — a pen, a brush, a guitar — and make something of your own. That, to me, is the mark of a good work. It doesn’t end when you close the book; it lingers, it moves you toward your own unfinished dream.

RiN may begin as a story about aspiring manga artists, but it’s really a story about staying alive through creation — about the courage to keep drawing even when no one is watching. And perhaps, somewhere within Norito’s determination and Rin’s quiet mystery, we can glimpse the artist himself — still chasing the same spark that lit his first page.

Stopper Busujima: The Rough Rhythm of the Underdog

Before Beck, before RiN, before the quiet depths of 7 Shakespeare, Harold Sakuishi had already been sketching his truth — in a place most wouldn’t think to look: the baseball field. Stopper Busujima was one of his earliest works, and in many ways, it already carried the pulse of everything that would later define him — the love for misfits, the belief in growth, and that rare empathy for those who start at the bottom.

The story follows Busujima Daihiro, a delinquent who’s expelled from high school without a single notable achievement to his name. By all accounts, he should’ve disappeared into obscurity. But fate, or maybe luck, gives him one more chance when Takeo Kogure, a veteran scout for the struggling Keihin Athletics, sees something in him. A spark, perhaps. Busujima joins the team — a weak, often-forgotten club — and from there begins the improbable climb toward greatness.

What makes Stopper Busujima so alive isn’t the baseball itself, but the texture of it. The sweat, the noise, the absurdity of locker-room dreams. Busujima isn’t a typical sports hero — he’s crude, impulsive, and stubborn. And yet, under the surface, there’s an unmistakable warmth. Through the guidance of a mascot named Chick-kun (who feels less like comic relief and more like a guardian spirit in disguise), Busujima begins to grow — not into a perfect athlete, but into a person capable of carrying both his anger and his promise.

There’s something endearingly old-fashioned about this manga. You can feel the era it was drawn in — the Pacific League of the mid-’90s, when players like Ichiro were still with Orix, when baseball wasn’t yet polished into spectacle. Sakuishi filled it with real names, real teams, small anecdotes that blur the line between fiction and memory. Reading it now feels like opening a time capsule — one where grit and humor coexisted freely, and the story didn’t try to impress you so much as entertain you with honesty.

It’s a baseball manga, yes — but it’s also Sakuishi’s early exploration of what would later become his signature: the underdog spirit. The same energy that powered Koyuki’s guitar and Fushimi’s pen once lived here in Busujima’s wild pitches. You can see it — that belief that greatness doesn’t always grow from talent; sometimes it grows from chaos, from failure, from the sheer stubbornness to keep trying.

And maybe that’s why Stopper Busujima remains so special. Beneath its rough art and straightforward storytelling lies a kind of sincerity that’s rare today. It reminds you of the time when stories didn’t need to be sleek — they just needed to mean something. Reading it feels like cheering from the stands for a player no one expects to win — and watching, amazed, as he somehow does.

Gorillaman: The Silence That Spoke Louder Than Words

People don’t really talk about Gorillaman anymore. It’s one of those names that has quietly slipped out of most conversations, yet still lives somewhere deep in the hearts of old-school manga readers. But make no mistake — this isn’t just some early experiment from Sakuishi-sensei. It’s another masterpiece, one that deserves to be remembered.

On the surface, Gorillaman sounds like pure comedy: a silent boy with a gorilla-like face transfers to Shiratake High and joins a group of delinquents. There are fights, pranks, wild faces, and bursts of slapstick. But beneath that chaos, there’s a tenderness — a strange, understated humanity. Sadaharu Ikedo, nicknamed “Gorillaman,” doesn’t speak a single word, and yet his silence becomes the manga’s pulse. The other characters shout, joke, fight, and grow around him, while he simply is calm in the middle of all that adolescent noise.

What’s remarkable is how natural it all feels. The world accepts him, readers accept him. No one questions why he doesn’t talk — because somehow, he communicates more clearly than anyone else. Through Sakuishi’s sharp expressions, body language, and comedic timing, Gorillaman becomes a mirror for everyone else’s madness. The humor lands with that precise sharpness you only find in old-school gag manga — those sudden bursts of absurdity followed by the tiniest flickers of realism. The “Becca” gag, the wild “Gory Special” wrestling moves, the ridiculous but strangely sincere fights — each of them was drawn with an artist’s intuition for rhythm. You can feel Sakuishi’s sense of timing, the same rhythm that later carried Beck’s music and RiN’s emotion.

It’s easy to forget how much Gorillaman achieved. In 1990, it won the 14th Kodansha Manga Award in the general category — and even now, it stands out for how it blends the rough and the delicate, the chaotic and the oddly poetic. For all its delinquent energy, it was never really a “Yankee manga.” It was about the everyday — the tiny, aimless dramas of high school life that somehow felt vast when you were living them.

And then, years later, Sakuishi returned to it — Gorillaman 40, a two-chapter revival that appeared in Weekly Young Magazine for its 40th anniversary. Suddenly, the silent boy was forty years old, an office worker with wrinkles where there used to be bruises. The fights had changed shape, the laughter had softened, but the soul was still there. When Fujimoto reminisces in the courtyard, and the manga cuts to a double-page flashback of their high school days, it feels like true time travel — not nostalgia, but continuity. You realize that you’ve grown older alongside them.

That’s the quiet brilliance of Sakuishi: he doesn’t just create characters; he creates lifetimes. In Gorillaman 40, the world has moved on — Fujimoto’s daughter is in high school, Junro is worried about his health, and the reckless energy of youth has turned into something gentler, something that aches in recognition. And still, the silent Gorillaman remains — unaging, wordless, unbroken.

I watched the trailer for Gorillaman 40 back in 2020, and it struck me how that same atmosphere still lingered — that strange mix of chaos and calm, laughter and loneliness. It reminded me that even without words, Sakuishi could still speak directly to the part of us that remembers who we were.

It’s been years since I first read it, but every time I think about those pages — the comedic frames, the quiet stares, the sudden seriousness — I feel that pull again. The kind that makes you say: I need to read it all over, from the beginning.

The Band: The Echo That Never Faded

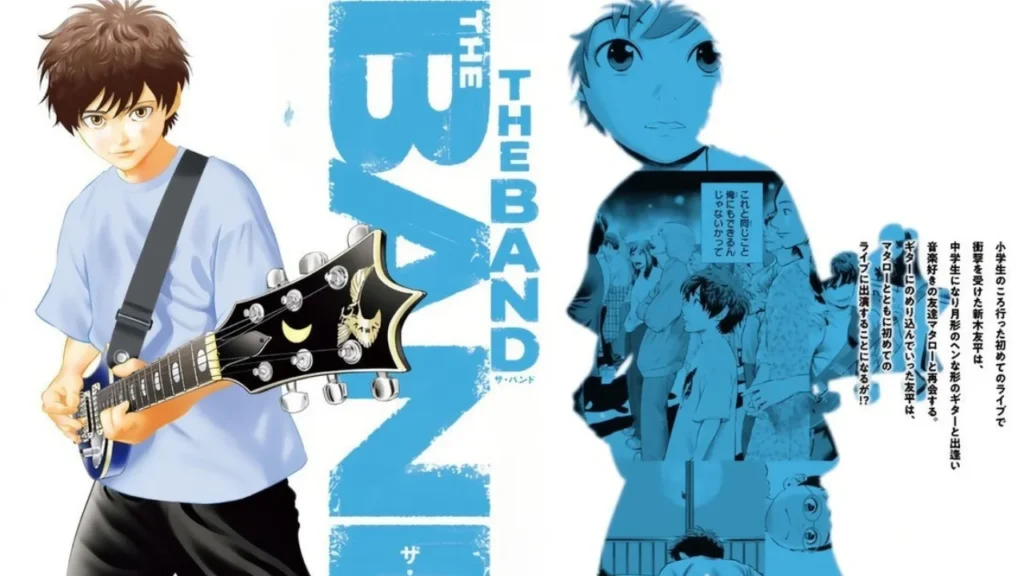

It’s strange how life circles back to the sounds that once defined it. When I heard that Harold Sakuishi was drawing another band manga — The Band — something inside me stirred, the way an old song sometimes does when you hear it again after years. He had said on TV that it might even cross paths with Beck, and of course, for someone who lived through those pages, there was no question of not reading it.

The story begins far from the glamorous light of the stage — with Yuhei Araki, a quiet fifth-grader from Nagoya. He’s bullied at school, living one of those small, gray lives that barely make a sound. But everything changes the day his mother takes him to a live concert. It’s one of those moments — sudden, electric, life-altering. He watches the band perform under the lights, and something in his chest cracks open. “Maybe I can do the same thing,” he thinks, and you can almost feel the spark leaping from the stage into his heart.

That spark is the beginning of everything. Yuhei meets Shintaro Iwata — “Mataro” — a fellow music lover who feels like a mirror of his own restless longing. The two connect instantly, only to be separated again, as if Sakuishi wants us to understand that music, like friendship, sometimes moves in echoes before it becomes harmony.

Time passes. Yuhei grows older, but the loneliness stays — until fate intervenes again. He finds a strange, crescent-shaped guitar — an object that feels almost supernatural — and soon after, he meets Mataro once more. Two miracles, one after the other. You can feel the air around him change. From there, The Band blooms like Beck once did — out of friendship, courage, and sound.

When I read it, I felt that same nostalgia I felt back when I first met Koyuki and Saku. The rhythm, the hope, the awkward beginnings of something that might become beautiful — it’s all there. But The Band isn’t just a repetition. It feels like a reflection — older, wiser, softer around the edges, but still burning. And the way this manga even came to be feels like destiny.

One Sunday, Sakuishi’s editor — a man who had also helped launch Beck — unexpectedly dropped by and said just one thing: “How about a music manga?” No long pitch, no planning, just that quiet suggestion. Later, the editor himself couldn’t even remember if he’d said it. But the words stayed with Sakuishi like a revelation, as if something — or someone — had whispered it from the other side of his memories. And so The Band was born.

It’s a story that carries both newness and nostalgia. Even though Sakuishi has said it will follow a different path from Beck, he’s hinted that the worlds may eventually cross — that we might, someday, glimpse Koyuki again. Just the thought of it feels like hearing a familiar guitar riff through a door that’s slightly ajar.

As of now, The Band has sold over 200,000 copies between its first two volumes — proof that people still want to hear Sakuishi’s voice. Volume 3 arrives this December, and I can’t wait. I want to see how Yuhei and Mataro grow, what becomes of their music, and whether those familiar faces from Beck appear like ghosts of old dreams.

Sometimes I think Sakuishi draws not just stories, but lifetimes — the same melody played across different generations. From Stopper Busujima to Beck, from RiN to The Band, his characters keep finding ways to believe in something again. Maybe that’s what his art really is — a long, unfinished song, one that keeps changing its chords but never loses its heart.

And as fans, all we can do is keep listening — waiting for the next note.

The Rest — For the Curious and the Completists

If you’ve already wandered through Beck, RiN, 7 Shakespeare, Stopper Busujima, and Gorillaman, and you still feel that small tug — that curiosity to know what else Sakuishi-sensei has drawn — then yes, there’s more. And if not, that’s perfectly fine too. These are works best read when you’re already a little bit in love with his world.

He began early — 1987, to be exact — with a debut called Sou Haikan (published under the name Tomoyoshi Sakuishi). It won the Young Artist Award at the 17th Chiba Tetsuya Awards, setting the stage for what would become a long, unpredictable journey. You can already sense the restless creativity there, the refusal to stay still.

Then came Hyenas of the Savannah in 1994 — a strange, fascinating experiment. It abandoned his usual art style for something bold and American-cartoon inspired, a visual departure that earned him praise from critics like Jun Ishikawa but didn’t quite find its footing with readers. The series ended midway, with Sakuishi humbly signing off with the words, “I’m sorry for not studying enough.” That line still feels telling — he was never afraid to try, even if it meant failing publicly. The story itself was an Arabian-style adventure set in the savanna, like Journey to the West retold under a blazing African sun. Imperfect, yes — but undeniably brave.

Later that same year, he returned to his original energy with Bakaichi — a martial arts tale about Kazuyoshi Ooba, the illegitimate son of a karate legend, trying to become the strongest man alive. It’s a story of sweat, grit, and personal evolution — full of the raw humor and spirit that mark Sakuishi’s best works. You can see him reclaiming his rhythm here, balancing wild energy with grounded emotion.

And somewhere in 2003, there’s a quieter, more personal piece: a one-shot titled Under the Bridge. It’s named after the Red Hot Chili Peppers song, which isn’t surprising, considering they’re Sakuishi’s favorite band. The story is autobiographical, recounting how he once met them at a concert and how that meeting somehow planted the seed that would grow into Beck. It’s short, intimate, almost like a diary entry disguised as a manga page — the artist looking back at the moment that changed his creative life.

So yes — these are the lesser-known Sakuishi works. You don’t have to read them all, but if you’ve already walked through his main worlds and still find yourself wondering what else he tried, these are the doors left ajar. Each one adds a note, a chord, to the larger song he’s been composing for decades — sometimes messy, sometimes offbeat, but always his own.

Closing Notes

Harold Sakuishi’s stories remind us that art doesn’t always begin in beauty — sometimes it begins in noise, in failure, in all the small, crooked corners of living. From the wild youth of Gorillaman to the quiet ambition of RiN, from Beck’s electric heartbeat to The Band’s echo of that same dream — he’s been telling us one thing all along: that creation itself is an act of survival.

His worlds may shift — from high school garages to Elizabethan stages, from baseball diamonds to concert lights — but the song remains the same. It’s about trying. About believing that something broken can still be tuned.

And if you’ve come this far with me — if you’ve read through Sakuishi’s worlds and still want to feel that rhythm — don’t forget to take a look at our anime & manga merch section, where we’ve created a special tribute line to Beck. It’s our small way of keeping that music alive — not just on the page, but in the world around us.

Because stories like these don’t end when you stop reading.

They keep playing — quietly, endlessly — somewhere inside you.