Life After Meaning: Reading Tsutomu Nihei in the Age of AI

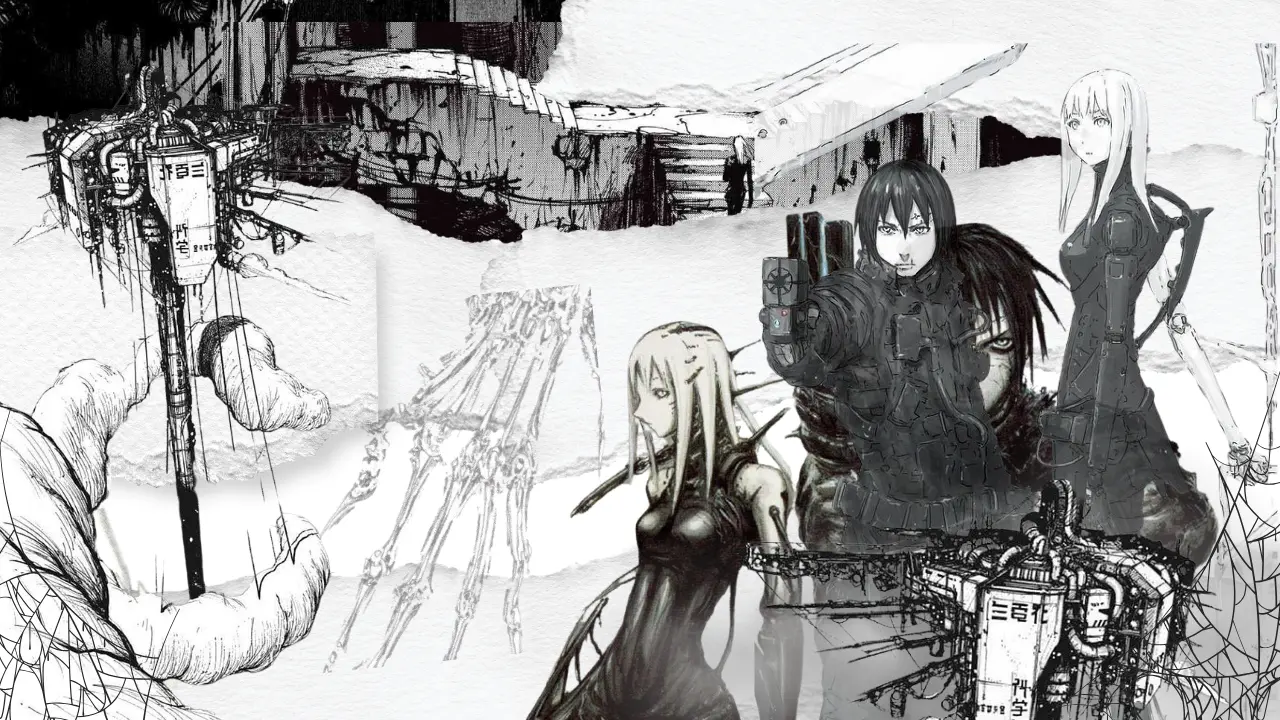

Tsutomu Nihei is often described as a master of hard science fiction, architecture, and silence. These descriptions are accurate, and yet they miss the deeper reason his work refuses to fade from memory.

Nihei does not merely depict bleak futures. He depicts a state of existence we already recognize.

In modern life, meaning has become strangely difficult to hold. Days are consumed by work whose consequences we cannot see, by routines that exhaust rather than fulfill, by endless WhatsApp, X, Instagram, Reddit, Facebook messages that prevent reflection without offering connection. We sense, vaguely but persistently, that we may have made a wrong turn somewhere, yet there is no moment quiet enough to examine it. The next day arrives before the question can even finish forming.

This is not an individual failure. It is structural.

As consumer society expands and social mobility increases, the frameworks that once anchored meaning nation, shared history, ideology, and even stable community have thinned or dissolved. Values fragment. What is “right” or “worthwhile” no longer converges. There is no longer a single answer to how one should live, and the absence of that answer is not replaced by freedom, but by exhaustion.

Nihei’s worlds feel familiar because they are built on the same condition.

His protagonists are also denied stable meaning. Companions die. Heroines are lost, absorbed, or merged with forces beyond human reach. Communities collapse or were never viable to begin with. Yet his stories are not tragedies. They are not even nihilistic.

What Nihei draws is life after meaning has already been taken away.

His worlds are dark, but they are not despairing. His characters continue; not because they believe things will improve, but because continuation itself becomes the only remaining form of agency. They move forward without reassurance, without explanation, without hope in the sentimental sense. And somehow, this persistence feels more honest than optimism.

This is the consciousness Nihei represents.

He does not ask how to find meaning. He asks how to remain alive when meaning is no longer guaranteed.

The secret sustaining his protagonists is not heroism. It is not faith. It is not moral certainty. It is a strange, stripped-down will that survives even when dreams collapse, communities fracture, and partners prove unreliable. His characters do not cling to a single pillar of meaning. They endure because their existence is distributed across goals, connections, and motion itself.

Nihei makes this survivable by design. Many of his protagonists are not fully human: safeguards, synthetic beings, clones, modified bodies created for specific purposes. Unlike us, they are born for something. Their existence is not accidental. To them, giving up is not an option because it was never encoded into them. By removing the possibility of existential doubt, Nihei isolates something essential: what action looks like when justification is no longer needed.

Why Nihei Feels Unsettling and Necessary Now

Nihei’s worlds resemble ours not because they look like it, but because they feel like it.

We inhabit systems we did not design and cannot meaningfully influence. We rely on technologies that increasingly resemble agency. We are surrounded by other people whose values feel alien, even when they are physically close to us. In such a world, meaning cannot be centralized; it must be distributed, balanced, and resilient.

Nihei’s works repeatedly circle three fragile supports of life:

- purpose (dreams)

- connection (community)

- intimacy (partners)

Each of these appears in his stories, and each of them is shown to be unstable on its own. What his narratives quietly suggest, without ever stating outright, is that survival in a post-meaning world depends not on purity or absolutes, but on balance. When one collapses, the others must compensate.

This is not a solution.

It is not comforting.

But it is honest.

And that honesty is why Nihei Tsutomu continues to haunt readers long after the final page.

NOiSE

Before the World Became Infinite

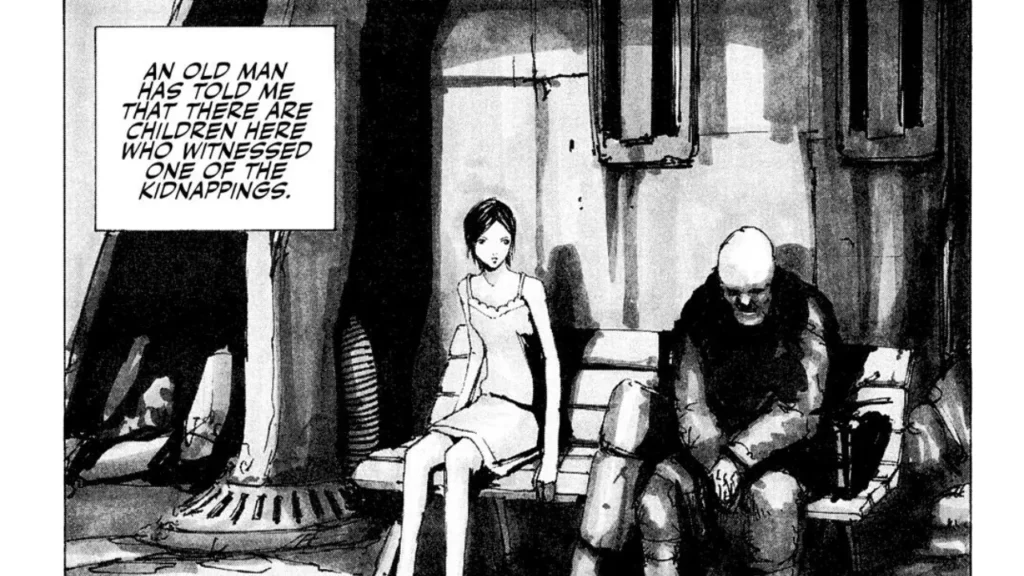

NOiSE is often introduced as a spin-off of BLAME!, but that framing undersells its importance. NOiSE is not an appendix; it is the moment before collapse, the last stage where causality, responsibility, and human institutions still vaguely function.

If BLAME! is a world where explanation has already failed, NOiSE is the point at which explanation is still possible but already insufficient.

This is why NOiSE feels so unsettling in a different way.

The city has not yet expanded into infinity. Architecture still obeys scale. Humans still occupy recognizable roles: police officers, administrators, and investigators. The Net Terminal Gene still matters, technology still has legal frameworks, and crime is still investigated rather than absorbed into the background noise of existence.

And yet, something is already irreversibly wrong.

A World Still Becoming and Already Breaking

What makes NOiSE extraordinary is that it depicts a society mid-transformation. This is not decay after the fact; it is decay happening in real time, while people are still trying to pretend the system works.

The setting is a future where technology has advanced to the point that humans can connect to the network without external devices. The boundary between body and system is already dissolving. Modification is no longer taboo; it is an aspiration. People desire transcendence, even if it requires sacrificing their biological integrity.

This is not framed as villainy.

It is framed as evolution under pressure.

Here, Nihei introduces a theme that will quietly govern all his later works:

progress does not ask whether humans are ready—it simply proceeds.

The result is not liberation, but instability.

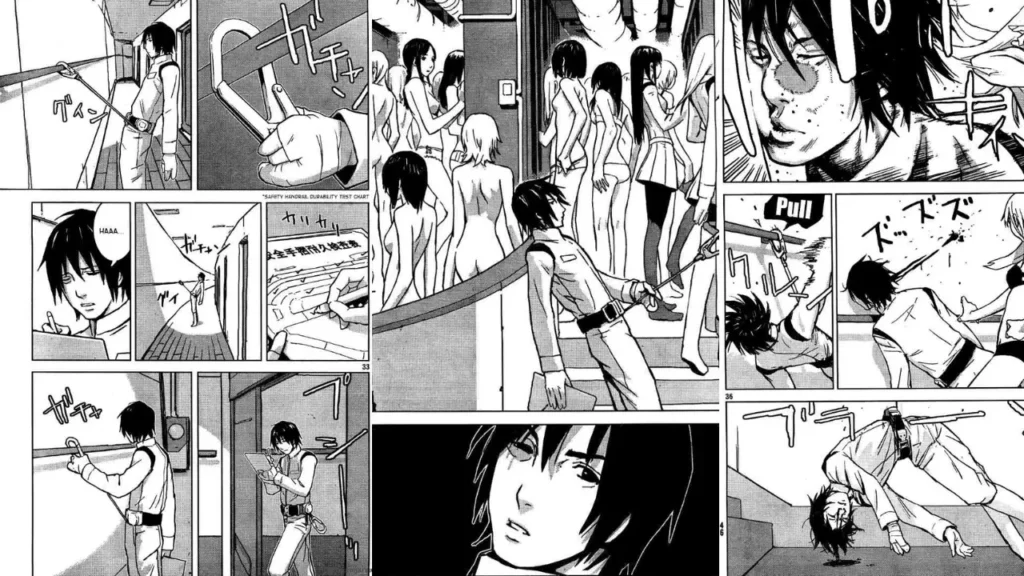

Susono Musubi and the Last Trace of Human Order

At the center of NOiSE is Susono Musubi, a police officer, an important choice. Police exist to preserve order, to impose narrative clarity: crime, investigation, cause, consequence.

Her case begins conventionally: a child abduction.

It ends with the discovery of murdered children, the disappearance of her partner Clawsa, and the erasure of the crime scene itself.

This is the crucial moment.

The system does not merely fail to protect.

It rewrites reality to remove the failure.

Musubi learns that she is no longer just an investigator; she has become a liability. Evidence disappears. Records are altered. The world begins to behave as if certain events should not be acknowledged at all.

This is not corruption in the usual sense. It is something colder.

Nihei is depicting the moment when systems stop caring about truth and begin prioritizing continuity. Once that shift occurs, justice becomes irrelevant. What matters is that the system keeps running.

Sound familiar?

The Birth of Nihei’s Central Question

What NOiSE captures better than any of Nihei’s later, more famous works is the moment when human meaning becomes incompatible with systemic logic.

Musubi still believes:

- Actions should have consequences

- Truth should matter

- Individuals should be accountable

But the world she inhabits no longer agrees.

This is why NOiSE is more explanatory than BLAME! not because Nihei became kinder to the reader, but because the world itself has not yet collapsed into abstraction. There is still something to explain.

And that is precisely what makes it tragic.

Musubi does not persist because she is invincible or programmed. She persists because she still believes her actions ought to matter. In this sense, she is closer to us than any of Nihei’s later protagonists.

She represents the last stage of human resistance before meaning gives way to motion.

From Ethics to Persistence

After NOiSE, Nihei’s protagonists will change. They will become less expressive, less socially embedded, and less recognizably human. Not because Nihei lost interest in humanity, but because he is tracking what happens after ethical frameworks collapse.

Susono Musubi’s struggle answers one question:

What does it look like when a human tries to preserve meaning inside a system that no longer supports it?

The rest of Nihei’s career asks a darker one:

What remains when that attempt fails?

That is where BLAME! begins.

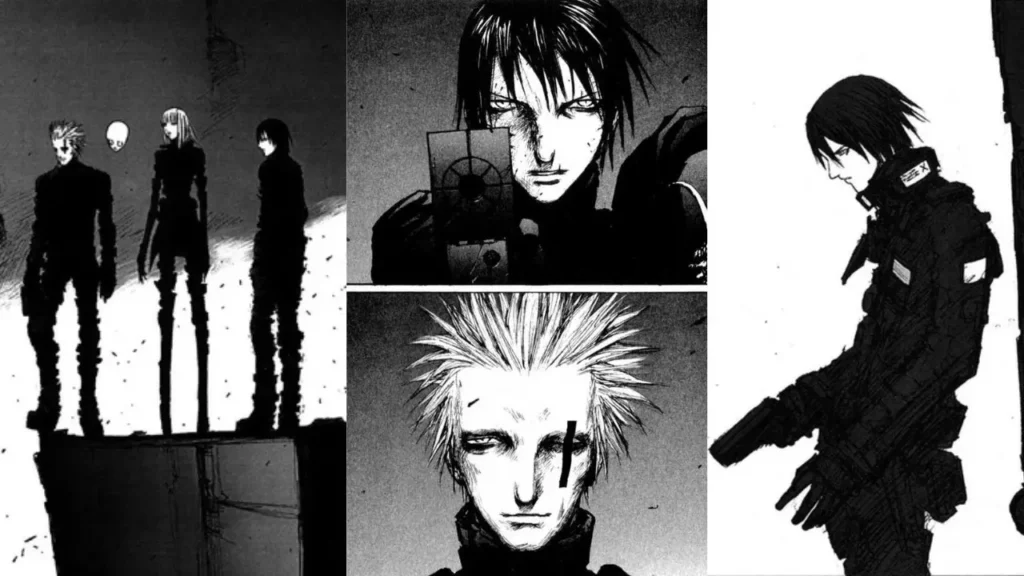

BLAME!

Movement After Meaning Has Collapsed

BLAME! begins where NOiSE ends: after ethics have failed, after institutions have dissolved, after explanation itself has become irrelevant.

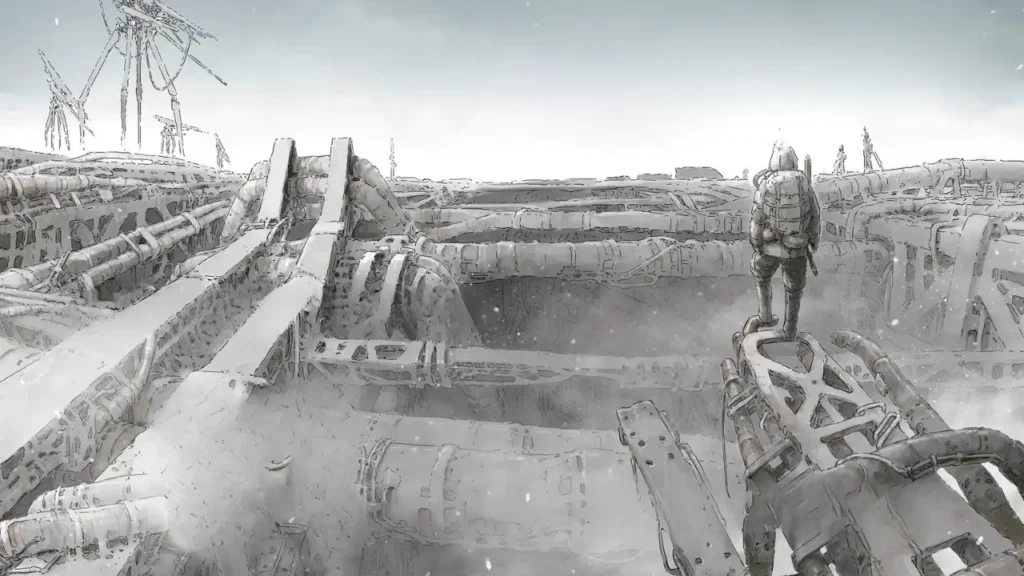

In the distant future, computer systems grew so complex that control was lost. Cities, once tools, became processes. Megastructures expanded vertically and horizontally without limit, layering themselves endlessly, floor upon floor, world upon world. What was once a managed environment became an autonomous one.

This is not a “ruined city.”

It is a city that will not stop growing.

At the center of this endless architecture moves Killy.

Killy is not introduced as a hero, nor even clearly as a human. He is an explorer, almost an algorithm given a body, tasked with searching for the Net Terminal Gene: a genetic key that would allow access to the Netsphere and restore control over the city’s systems. He moves through thousands, tens of thousands of floors, following an order so old that its origin no longer matters.

What matters is that he moves.

A World Without Narrative Privilege

Unlike most science fiction protagonists, Killy is not granted narrative comfort. There is no clear timeline, no map, no reassurance that progress is being made. Dialogue is sparse. Exposition is minimal. The reader is placed in the same position as Killy: surrounded by overwhelming scale, deprived of context, forced to infer meaning from fragments.

This is intentional.

Nihei does not want you to understand the world of BLAME! in a conventional sense. He wants you to experience what it is like to exist inside a system that no longer recognizes you.

The Netsphere once governed reality. After the Calamity, it malfunctioned. Humans lost access when the Net Terminal Gene mutated. The Safeguard, originally a defense system, continued its function without discrimination, exterminating humans who no longer met its criteria. Silicon-based lifeforms, thriving on chaos, further destabilized the world.

What emerges is not good versus evil, but process versus presence.

No faction is morally centered. Everyone is responding to systems larger than themselves.

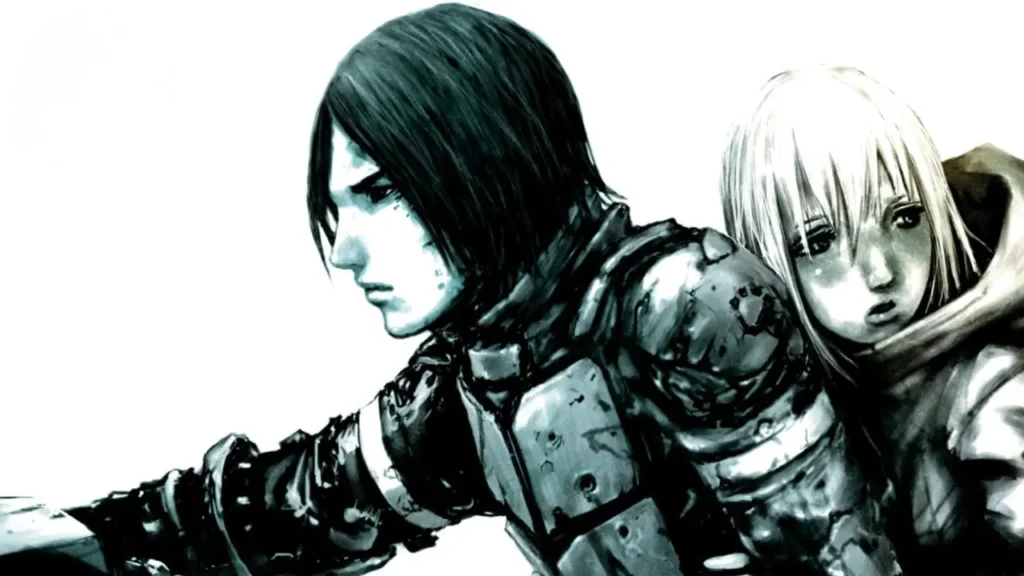

Killy as Post-Human Will

Killy does not question his goal. He does not grieve in ways the narrative lingers on. Even when companions are lost, even when Shibo, a scientist who briefly restores something like dialogue and relational warmth, is assimilated and destroyed, Killy continues.

This is often mistaken for emotional emptiness.

It is something else.

Killy embodies a form of existence where will has outlived meaning. He does not move because he believes the world can be saved in any romantic sense. He moves because stopping would negate his entire mode of being.

This is why Killy feels closer to an android than a man and why that matters.

Nihei constructs Killy as a being who cannot afford existential doubt. His purpose is embedded, not chosen. In doing so, Nihei removes the most paralyzing modern question, “Is this worth it?” and replaces it with something colder but more durable: “This is what I do.”

In a world where meaning has become impossible to verify, persistence becomes the only proof of existence.

Architecture as Fate

The megastructure is not the background. It is destiny.

Endless corridors, vertiginous shafts, impossible staircases, these are not aesthetic indulgences. They express a world where scale has surpassed human relevance. No one designed this city with Killy in mind. No one will notice if he fails.

And yet, the city is not empty. It is dense with information, function, and latent power. Every panel is overloaded with detail, forcing the reader to slow down, to look, to search just like Killy.

This is why BLAME! transcends language. Meaning is not carried by dialogue but by density. The act of reading becomes physical labor. You don’t consume BLAME!; you traverse it.

Shibo, the Embryo, and Deferred Hope

Hope in BLAME! is never triumphant. It is postponed.

Shibo’s failure to access the Netsphere does not resolve anything. Her assimilation into the Safeguard does not reverse the system. Even the spherical embryo Killy, recovers implied to contain the potential to restore control, is not celebrated.

It is carried forward.

The journey toward a place “beyond the megastructures,” where infection may not exist, is not an ending. It is a continuation. The possibility of restoration is deferred, not achieved.

Nihei refuses closure because closure would be dishonest.

BLAME! as the Purest Expression of Post-Meaning Life

If NOiSE shows us the last moment where justice still feels imaginable, BLAME! shows us life after justice has been replaced by function.

This is why BLAME! feels eerily contemporary in the age of AI.

We live inside systems that continue regardless of our understanding. Algorithms optimize outcomes without explaining values. Work persists even when its purpose is unclear. Technologies advance faster than ethical frameworks can adapt.

Like Killy, we are often moving through structures we did not build, following objectives we inherited rather than chose.

And yet we continue.

Not because we are hopeful.

Not because we are certain.

But because motion itself has become survival.

That is the quiet truth, BLAME! articulates better than almost any modern fiction.

Biomega

When Persistence Learns to Interfere

Biomega does not abandon the world of BLAME! It reacts to it.

If BLAME! depicts existence after control has vanished. Biomega asks a different question:

What happens when humanity tries to intervene again?

The year is 3005. Civilization has already suffered a quiet collapse, not through war, but through data terrorism. Authority has condensed into institutions like the Data Recovery Foundation (DRF), organizations that exist not to create futures, but to manage damage. Humanity’s first manned return from Mars in seven centuries should be a triumph. Instead, it becomes the vector for N5S, a virus that triggers the Drone Plague, an outbreak that does not merely kill, but transforms.

This is Nihei’s first full confrontation with biotechnology as destiny.

From Infinite Space to Unstable Life

Visually, Biomega resembles BLAME! the same compressed panels, the same obsessive architecture, the same overwhelming sense of distance. But something fundamental has changed. Where BLAME! was dominated by inorganic systems—megastructures, networks, safeguards—Biomega is saturated with organic instability.

Bodies mutate. Viruses evolve. Life itself becomes the site of conflict.

Nihei is no longer depicting a world where systems have escaped humanity. He is depicting a world where humanity keeps touching systems it does not fully understand and suffering the consequences.

Zoichi and the Return of Agency

Kanoe Zoichi, a synthetic human dispatched by Toa Heavy Industries, marks a subtle but critical shift in Nihei’s protagonists. Like Killy, Zoichi is artificial, task-oriented, and resistant to existential hesitation. But unlike Killy, Zoichi does not merely traverse the world; he intervenes in it.

He rides a motorcycle through collapsing structures. He wields the Projectile Acceleration Device with precise, almost stylish lethality. He is accompanied by Kanoe Fuyu, an AI presence that does something unheard of in BLAME!: she converses, supports, and reflects.

This matters.

Biomega introduces dialogue not as comfort, but as complication. With communication comes disagreement, intention, and conflict between visions of the future.

Immortality as the Central Temptation

At the heart of Biomega is a three-way ideological conflict:

- Nyaldee / DRF: rejects immortality, seeks to transform Earth itself into a higher-order environment

- Narain / Public Health Bureau: promotes immortality through the Total Human Regeneration Plan

- Toa Heavy Industries attempts to protect humanity from both extremes while relying on the same technologies

What makes Biomega unsettling is that none of these positions is cartoonishly wrong.

In fact, Nyaldee’s opposition to immortality, despite its violence, often feels more grounded than Narain’s pursuit of endless life. Immortality is revealed not as salvation, but as a technology that multiplies unintended consequences. Most of humanity does not become immortal. Instead, new monsters, hybrids, and unstable beings emerge.

This is Nihei’s clearest statement yet about technology:

Technology does not simply fulfill intentions.

It produces excess.

The world of Biomega is not destroyed by evil. It is destabilized by outcomes no one fully planned for.

A Love Story Buried Inside Systems

What you noticed about Loew and Reload is crucial and rarely discussed.

At its core, Biomega may be Nihei’s most twisted love story.

Loew’s desire to become immortal and reach Mars is never framed as ideological. It feels personal, almost embarrassingly so. Reload’s departure, her connection to the ovule on Mars, and the way their bond echoes through Nyaldee and Narain all suggest that grand technological programs may originate in private longing.

If that reading is correct, then Biomega becomes devastating:

entire civilizations reshaped by unresolved intimacy.

Technology here is not neutral. It is haunted.

Distance, Compression, and the Pleasure of Excess

Formally, Biomega may be Nihei at his most indulgent and most rewarding.

Panels are so dense that they stain your fingers. An EXIT sign casually reading “10,000m to the exit” does more philosophical work than pages of dialogue ever could. Distance becomes absurd, oppressive, and almost comic. You can see the end, but you cannot reach it.

Even language mutates. Terms like “Manner Mode,” once signifying restraint, are repurposed into lethal functionality. Meaning is not erased; it is reassigned.

This is Nihei’s quiet genius: he never tells you that words, bodies, or technologies have changed. He lets you feel it.

Biomega as the Turning Point

If BLAME! is existence without intervention, Biomega is existence overloaded with intervention.

Here, persistence alone is no longer enough. Choice enters the system and with it, error, excess, and responsibility. The world does not improve. It becomes more complex, more unstable, more alive.

And this prepares us for Nihei’s next move:

the return of community.

That is where Abara begins.

Abara

The Body as the Last Remaining Meaning

If BLAME! is movement without meaning, and Biomega is meaning destabilized by intervention, Abara is what remains when even systems fall away.

There are no megastructures endlessly expanding here.

No global institutions.

No ideological factions were carefully articulated.

There is only the body, pushed to its absolute limit.

A World Without Distance

One of the first things you notice in Abara is how small the world feels compared to BLAME! or Biomega. Not safer, just closer. Violence happens at arm’s length. Transformation happens inside flesh, not across infrastructure.

Nihei abandons infinite architecture and instead draws compression:

- streets instead of megacities

- encounters instead of journeys

- eruptions instead of processes

This is deliberate. After worlds defined by systems, Abara asks:

What if meaning has nowhere left to hide except the body itself?

Black Gaunas and the Collapse of Identity

The Black Gaunas (or Black Kikkoku) are not machines, not quite humans, and not symbols of progress. They are threshold beings, hybrids born from necessity, mutation, and violence.

They do not choose what they are.

They activate.

This activation is not heroic. It is grotesque, painful, irreversible. Bones tear through skin. Forms reconfigure mid-combat. Power arrives as loss of stability, of humanity, of continuity.

And yet, this transformation is not framed as tragedy.

It is framed as an adaptation.

Nihei is asking something uncomfortable here:

If the world no longer guarantees meaning, does survival justify becoming something else entirely?

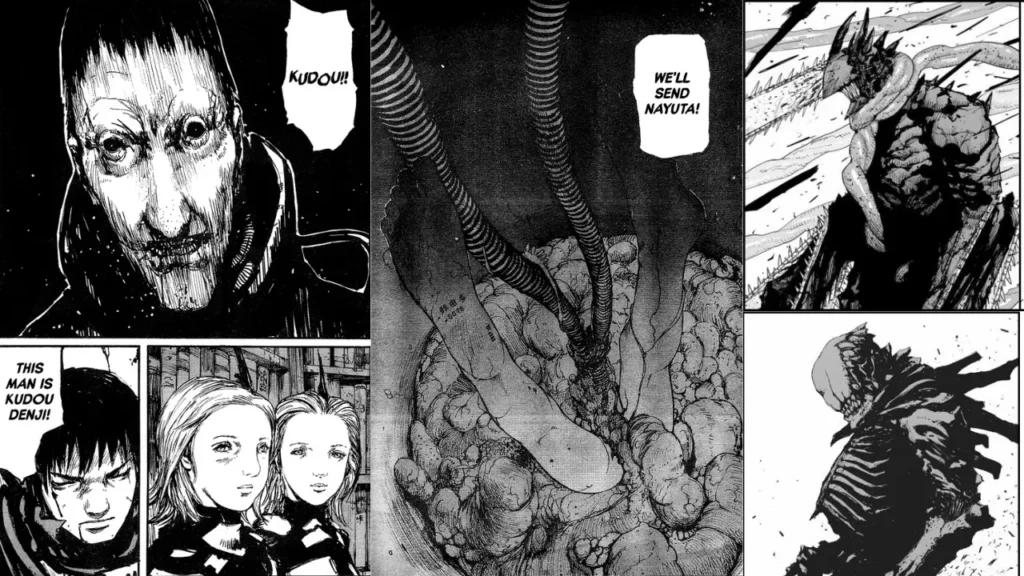

As a brief but intriguing aside: the two Black Gauna in Abara are named Denji and Nayuta. For readers of Chainsaw Man, those names immediately ring a bell.

This is not accidental.

Tatsuki Fujimoto has gone on an interview saying that Abara deeply influenced him, and the reuse of these names feels less like a reference and more like a quiet salute. In Chainsaw Man, Denji and Nayuta exist in a completely different genre, tone, and narrative structure, but they carry the same underlying tension: bodies pushed beyond humanity, identities forged through violence, and survival divorced from moral clarity.

Seen this way, Abara becomes more than a cult Nihei work. It quietly seeds ideas that later bloom in one of the most influential manga of the modern era. Not as imitation, but as inheritance.

Denji and Action Without Justification

Denji, like Killy and Zoichi before him, does not spend time reflecting on his role. But unlike them, Denji does not even have the comfort of a system or a mission handed down from above.

His existence is reactive. Immediate. Violent.

In Abara, there is no long-term plan. There is only the next confrontation, the next transformation, the next moment of survival. Time collapses into intensity.

This makes Abara feel almost mythic, not because it reaches backward, but because it strips life down to gesture and consequence.

The Adam and Eve Ending

The final implication that Sakijima and Tadohomi may escape into another world and become something like Adam and Eve is easy to misread as hope.

It isn’t.

It’s reset.

Nihei is not promising salvation. He is suggesting that when systems fail completely, the only remaining option may be starting again without guarantees.

No grand ideology.

No technological utopia.

Just beings, bodies, and the possibility of continuation.

Why Abara Matters

Abara is often treated as a side work too violent, too opaque, too short. That’s a mistake.

It is Nihei’s pressure test.

He removes:

- architecture (BLAME!)

- ideology (Biomega)

- institutions (NOiSE)

and asks whether persistence still exists.

It does.

But it exists only as embodied will.

The Bridge to Knights of Sidonia

This is why Abara must come before Knights of Sidonia.

Only after stripping life down to the body can Nihei reintroduce:

- society

- reproduction

- routine

- community

Knights of Sidonia is not a softening.

It is a reconstruction, built on the ruins that Abara exposes.

Knights of Sidonia

When Persistence Becomes Communal

If Abara reduces existence to the body alone, Knights of Sidonia asks what happens when bodies are forced to live together again.

A thousand years have passed since the Gauna destroyed the solar system. Humanity did not rebuild; it fled. What remains of the species survives aboard seed ships, artificial worlds drifting endlessly through space, searching not for victory, but for somewhere stable enough to continue.

Sidonia is one such ship.

It is not a city in the BLAME! sense, nor an experimental battleground like Biomega. Sidonia is something far more fragile: a closed ecosystem. Population, reproduction, labor, memory, everything must be managed, recycled, and optimized. There is no outside world left to retreat to.

For the first time in Nihei’s work, survival is no longer individual.

A Protagonist Born Inside the System

Tanikaze Nagate enters the story from below literally. A non-regular resident raised in the depths of Sidonia’s understructure, he emerges into society almost as a relic, someone shaped by isolation rather than design.

This matters.

Unlike Killy, Zoichi, or Denji, Tanikaze is not created for a task. He is absorbed into one. By chance and circumstance, he becomes a trainee Guardian pilot, drawn into Sidonia’s frontline war against the Gauna.

With this shift, Nihei changes something fundamental: the protagonist is no longer alone.

Community as Necessity, Not Comfort

Knights of Sidonia shocked many readers on release. A Nihei manga with:

- a school setting,

- romantic tension

- comedic beats

- “moe” character designs

On the surface, it looked like capitulation.

It wasn’t.

Sidonia’s school-life structure is not there to soften the world; it exists because training, bonding, and reproduction are survival mechanisms. Romance is not indulgence. It is logistics. Gender itself becomes adaptive: humans who photosynthesize, and “neutrals” who determine sex through relational contact.

Even intimacy is systematized.

Nihei has not abandoned ruthlessness. He has redistributed it.

Violence Without Narrative Protection

The Guardians Sidonia’s giant humanoid weapons might suggest classic mecha heroism. Instead, Nihei turns them into instruments of attrition. Battles are sudden, lethal, and unfair. Major characters die without ceremony. Skill does not guarantee survival.

What’s unsettling is the contrast.

In one chapter, characters joke, flirt, and argue over crushes.

In the next, they are erased.

Nihei is not juxtaposing light and dark for drama. He is showing what it means to live inside a world where life must continue even as death remains arbitrary.

Community does not protect you from loss.

It only ensures that life goes on after it.

Sidonia as the First Stable World and Its Cost

Sidonia succeeds where previous worlds failed because it eliminates variables. There is no migration. No ideological diversity. No external economy. It is a sealed loop.

This is why Knights of Sidonia can depict something Nihei previously avoided: routine.

Meals. Training schedules. Dorm rooms. Gossip.

But this stability comes at a price. Sidonia is safe only because it is closed. Individual freedom is secondary to species continuity. The community survives precisely because it cannot afford fragmentation.

Nihei does not present this as utopia.

He presents it as the least catastrophic option available.

Why This Work Matters in the Age of AI

In the age of AI, automation, and managed populations, Knights of Sidonia feels disturbingly prescient.

Sidonia is a world where:

- Roles are assigned based on system needs

- Bodies are modified for efficiency

- Reproduction is regulated

- Individuality exists, but only within tolerable bounds

And yet people fall in love. They hesitate. They grieve. They choose, even when choices are constrained.

Nihei’s insight here is subtle but profound:

Meaning does not return through freedom.

It returns through shared vulnerability.

Unlike Killy’s solitary persistence or Denji’s embodied violence, Tanikaze survives because others exist alongside him. Not to save him but to witness him.

Knights of Sidonia as Reconstruction

Seen in the context of Nihei’s full trajectory:

- NOiSE — ethics begin to fail

- BLAME! — movement replaces meaning

- Biomega — intervention destabilizes the world

- Abara — the body becomes the last refuge

- Knights of Sidonia — society is rebuilt under constraint

This is not a retreat into accessibility.

It is a reassembly of life, done cautiously, painfully, and without illusion.

And crucially: it is not the end.

Because once a community exists, it creates new tensions: inheritance, evolution, succession.

That brings us to Nihei’s most austere and one of his final meditations.

Aposimz

The Last World, and the Question That Remains

If Knights of Sidonia is about rebuilding life inside a closed system, Tsutomu Nihei’s latest long-form work, Aposimz, asks a harsher question:

What happens when even reconstruction is no longer guaranteed?

The setting is an artificial celestial body, Aposimz, so vast that most of its mass lies underground, sealed beneath a superstructure shell. Fifty centuries ago, humanity lost a war against what is only called “the underground.” The result was not extinction, but exile. Humans were stripped of the right to inhabit the world they once controlled and forced to survive on the frozen surface.

This is important:

Aposimz is not a story about the end of the world.

It is a story about being denied the right to live properly inside it.

A White World After Black Ones

Nihei himself has remarked that until now, his worlds were black, dense, shadowed, and claustrophobic. Aposimz is different. It is overwhelmingly white.

Snowfields. Blank skies. Empty horizons.

This is not emptiness as peace. It is emptiness as exposure. Where BLAME! overwhelmed the reader with density, Aposimz unsettles by withholding information. Fewer visual cues. Fewer explanations. Fewer places to hide.

Meaning is not buried under excess here.

It is lost in openness.

Etherow and the Burden of the Code

The protagonist, Etherow, begins not as a chosen one but as a survivor. He lives with others on the White Diamond Beam, scraping out an existence amid scarcity, automatons, and a strange affliction known as Frame Disease.

Then he meets Titania.

Like many Nihei heroines, she arrives abruptly and vanishes just as quickly. Before disappearing, she entrusts Etherow with a “Code,” a word that carries weight long before its function is explained. When the Liberdoa Empire hunts him for it, Etherow loses everything: his home, his companions, his former life.

Revenge follows—but revenge here is not empowerment.

It is a burden.

Etherow is transformed into a “regular doll,” clad in ena, wielding Higgs-based weaponry. Familiar terms echo earlier works, Sidonia, Biomega, but stripped of their institutional context. Technology here no longer belongs to a system. It attaches directly to the body.

Fantasy, But Not Escape

On the surface, Aposimz looks like a departure. There are empires, marching armies, and revenge arcs. The atmosphere recalls Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, a devastated ecology, a lost civilization, humanity living among the ruins of its own ambition.

But Nihei has not softened. He has condensed.

Dialogue is minimal. Concepts appear without explanation. The reader is not guided; they are absorbed. You begin to accept the world not because you understand it, but because that is how people inside it must live.

This is Nihei’s greatest trick: he does not explain the world; he normalizes it.

Titania, Mascots, and Deferred Truth

Titania’s return in a mascot-like form is easy to misread as whimsy. It is not. It is displacement.

She claims to come from the Central Control Layer, the unreachable heart of Aposimz. She speaks of the world ending, but never in ways that grant clarity. As always, Nihei refuses revelation. Knowledge exists, but it is unevenly distributed, and never where you want it.

The Liberdoa Empire’s pursuit of her is not explained as ideology or evil. It is procedural. Like the Safeguard. Like the Gauna. Like the DRF. Power continues to move, even when meaning has fractured.

Living After Defeat

The most devastating line in Aposimz’s opening is not about war or machines. It is this:

“But people still managed to continue to live.”

This has always been Nihei’s subject.

In NOiSE, people tried to preserve justice.

In BLAME!, they moved without understanding.

In Biomega, they intervened and created excess.

In Abara, they survived as bodies.

In Knights of Sidonia, they rebuilt the community.

In Aposimz, they live after losing even the right to belong.

There is no promise of restoration here. No clear endpoint. Only continuation—again.

Why Aposimz Feels Like an Ending

Aposimz feels unfinished, not because it lacks answers, but because it refuses to pretend answers are coming.

This is Nihei at his most distilled:

a world where meaning, systems, and even reconstruction are provisional, and yet life persists.

Not heroically.

Not optimistically.

Simply, stubbornly.

That is why Aposimz feels less like a new chapter and more like a final question left open.

Kaina of the Great Snow Sea, Tower Dungeon, and the Late-Phase Nihei

After Aposimz, Tsutomu Nihei does something unexpected. He does not escalate the scale. He does not darken tone. Instead, he changes genre shells while keeping the same internal logic intact.

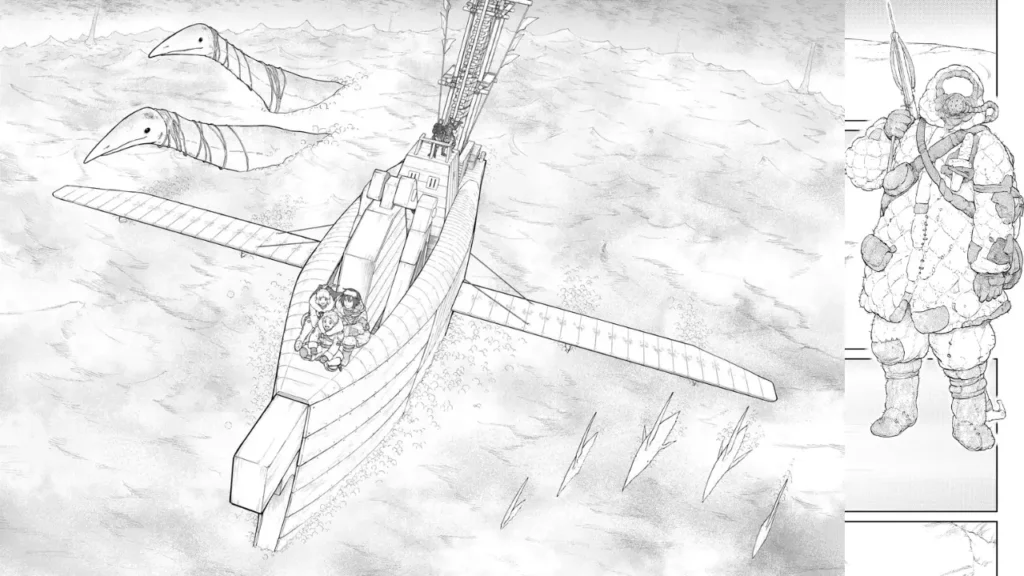

Kaina of the Great Snow Sea

A World That Asks to Be Shared

What makes Kaina of the Great Snow Sea remarkable is not just its setting, but its origin. In an era where animation increasingly adapts existing manga or novels, Kaina begins as an original animated work, a world created not for adaptation, but for discovery.

At first glance, it looks like classic fantasy: a boy, a girl, a meeting that changes the fate of the world. But Nihei never tells familiar stories without unsettling them.

The world is split vertically.

Above: a fragile civilization clinging to the sky, living among colossal Orbital Trees beneath a transparent celestial membrane.

Below: a frozen surface buried under an endless Sea of Snow, where water scarcity determines survival.

Kaina and Liliha are not just from different cultures; they are from different ontological layers of the same ruined world.

This is Nihei doing something new: instead of isolating the protagonist inside a system, he forces connections across systems.

Where earlier works asked, “How does one persist alone?”

Kaina asks, “What happens when survival depends on understanding someone from an entirely different world?”

The conflict is not metaphysical this time. It is ecological. Water replaces data. Trees replace networks. Scarcity replaces abstraction.

And yet, Nihei’s old obsessions remain:

- lost civilizations hinted at through signage and unreadable text

- literacy as power (Kaina alone can read the signs)

- maps hidden inside ruins

- salvation deferred, never guaranteed

Even the Great Orbital Tree is not framed as a miracle, but as the least catastrophic possibility.

If Aposimz depicts life after defeat, Kaina depicts life after misunderstanding and suggests that meaning might re-emerge not through dominance, but through translation.

Tower Dungeon

When Nihei Turns the RPG Inside Out

At first glance, Tower Dungeon feels almost mischievous.

A fantasy kingdom.

A kidnapped princess.

A massive tower divided into floors.

Monsters. Loot. Rival adventurers.

Everything about it screams “classic RPG.”

And that is precisely the trap.

Nihei has always loved structures, megastructures, ships, and cities. The Dragon Tower is simply his purest structure yet: a vertical world reduced to function. Floors exist to be cleared. Stairs exist to be guarded. Progress is measured spatially, not morally.

Yuva, the protagonist, is not special by destiny. He is strong, yes, but strength here is a resource, not a virtue. Allies betray each other. Towns spring up opportunistically at the tower’s base. Exploration becomes economy.

Even heroism is monetized.

What Tower Dungeon quietly exposes is how quickly meaning collapses into incentive systems once a structure promises reward. The proclamation “Whoever rescues the princess shall inherit the throne” does not create heroes. It creates congestion.

This is Nihei returning, once again, to the same question he has always asked:

What happens to purpose once it becomes measurable?

The Dragon Tower is not evil. It is indifferent. And like all indifferent systems, it invites exploitation.

Closing Reflection

| Manga Title | Protagonist | Primary Antagonist/Threat | Key Technology/Concept |

| NOiSE | Susono Musubi | The Order / Early Silicon Life | The Netsphere / Netsphere Privileges |

| BLAME! | Killy (Kyrii) | The Safeguard / Silicon Creatures | Net Terminal Gene / GBE |

| Biomega | Zoichi Kanoe | DRF / Nyaldee | N5S Virus / Toa AI Motorcycle |

| Abara | Denji Kudou | White Gauna / Ayuta | Bone Armor / Mausoleums |

| Knights of Sidonia | Nagate Tanikaze | Gauna (Alien) / Ochiai | Garde (Tsugumori) / Photosynthesis |

| Aposimz | Etherow (Esurō) | Rebedoa Empire | Regular Frames / Heigus Particles |

| Kaina | Kaina | Valghia | Orbital Spire Trees / Canopy |

| Tower Dungeon | Yuva | Necromancer / Monsters | Dragon Tower / Looting Mechanics |

Why Nihei Tsutomu Could Only Exist Like This

Tsutomu Nihei could only have emerged as a manga artist, and not because manga is flexible, visual, or commercially forgiving—but because manga allows silence to remain intact.

His work resists explanation in the same way real life does. There are no omniscient narrators in our lives, no clean chapter breaks that tell us what mattered and what didn’t. Meaning does not arrive annotated. It accumulates if it does at all through motion, proximity, and repetition. Manga, more than film or prose, allows this accumulation without forcing interpretation. Panels can linger. Pages can breathe. Vast spaces can remain empty without demanding justification.

This is why Nihei’s work so often resists adaptation. Animation smooths edges. Film requires rhythm. Dialogue demands motivation. But Nihei’s worlds are not built on rhythm or motivation; they are built on conditions. They are environments you survive inside, not stories you consume.

Across NOiSE, BLAME!, Biomega, Abara, Knights of Sidonia, Aposimz, Kaina, and even Tower Dungeon, one truth becomes impossible to ignore:

Nihei is not asking us to understand his worlds.

He is asking whether we can continue living inside ours.

In the age of AI, this question sharpens.

We are surrounded by systems that optimize without empathy, decide without explanation, and persist without meaning. We are told that creativity can be generated, labor replaced, even intimacy simulated. The boundary between human and machine—something Nihei dismissed decades ago as already meaningless has finally begun to dissolve in daily life.

And yet, here we are. Still waking up. Still moving. Still choosing, however imperfectly.

Nihei never offers a solution to this condition. He does something far more honest. He shows us characters who persist without certainty, who form fragile communities without guarantees, who love without promises, who act without assurance that their actions will matter.

In his world, hope is not a light at the end of the tunnel.

It is the tunnel continuing.

Perhaps that is why his work stays with us long after we finish reading. Not because it answers anything but because it mirrors the shape of our own lives with unsettling accuracy. We, too, move through systems we did not design. We, too, inherit objectives without origins. We, too, survive amid ruins that no longer explain themselves.

And yet, like Killy walking forward, like Yui refusing to forget, like Zoichi intervening, like Tanikaze choosing to stay, like Etherow standing up again, we continue.

Not heroically.

Not optimistically.

Just stubbornly.

That may be Nihei Tsutomu’s quietest, and most human, truth: that in a world where meaning is no longer given, continuation itself becomes an act of defiance.

And perhaps, for now, that is enough.