The Art and Legacy of Shinichi Sakamoto: A Definitive Deep Dive

Where most manga artists work within the limits of the medium—accepting that panels will shrink, tones will blur, and detail will flatten—Shinichi Sakamoto works against those limits. His pages are not merely illustrations to be printed; they are attempts to overwhelm reproduction itself.

Every lock of hair, every thread of lace, every ripple of stone or flesh is drawn as though the paper is only temporarily holding it. This is why readers come away from his books with a strange sense of both awe and frustration: awe at the beauty captured, frustration at the beauty that can’t quite be seen.

To read Sakamoto is to feel like you are always holding only part of the work in your hands, with the rest vibrating just out of reach. That tension—between what fits on the page and what refuses to—is what makes him one of the most singular figures in contemporary manga.

Biography & Career Phases of Shinichi Sakamoto

Born: July 19, 1972 — Osaka Prefecture.

Shinichi Sakamoto’s career is a study in reinvention: from a confident high-school artist in Osaka to a humbled assistant in Tokyo, a long, exploratory “dark” period, and finally to the painter-mangaka whose pages now travel museum walls.

1. Rookie Pride and the Jump Years (1990–1995)

As a high-schooler, Sakamoto proudly considered himself the best artist at his school. After deciding to become a mangaka, he submitted Keith!! and won a Weekly Shōnen Jump rookie prize (the Hop☆Step Award), which pushed him to move to Tokyo and try his luck professionally.

In Tokyo, he worked as an assistant to Tatsuya Egawa (Golden Boy) and made friends with fellow Jump hopefuls like Kazutoshi Yamane and Takashi Noguchi. Early short stories and one-shots from 1991–1994 were collected as Bloody Soldier; one story, Mortal Commando GUY, proved popular enough to expand into a full run in 1995.

2. Influence, Imitation, and the Long Dark (mid-90s → mid-2000s)

Sakamoto’s earliest pages show the clear influence of Tetsuo Hara’s muscular, fighting-manga model. He has openly said he “was drawing borrowed pictures” — chasing the anime-style and the trends that seemed to win serialization and sales.

To support himself, Sakamoto became an apprentice to Egawa Tatsuya (Golden Boy). But instead of confidence, the job brought a harsh reality check: every other assistant outshone him. His pride crumbled.

Working as an assistant under Egawa only sharpened the tension: Egawa’s clean, flowing lines were the opposite of Sakamoto’s more emotional approach, and the apprenticeship period left him feeling as if he was losing his own voice.

For nearly a decade, he suppressed his instincts to chase popularity—an approach that dragged on for twenty years without real success. He later described this as his “dark period,” when his characters felt lifeless and his work disposable.

3. Rediscovering Himself: Partnership and Reflection (late 2000s)

The turning point came when he met his wife, also a manga artist. The two moved in together and spent their days studying manga methodology instead of socializing. It was during this time that Sakamoto glanced at the spine of one of his early short story collections of Bloody Soldier and felt a jolt of recognition: “Maybe this is my picture.”

This realization pushed him to draw what only he could create, rather than mimic trends. Returning to his roots gave birth to the faces of Buntarō Mori in The Climber (Kokou no Hito) and Charles-Henri Sanson in Innocent.

4. Breakthrough with The Climber (2007–2011)

Even with this newfound artistic direction, Sakamoto confessed he lacked something deeper to communicate. That changed with The Climber. While working on the series, his personal experiences and emotions began flowing directly into the manga. For the first time, his art and his daily life intertwined.

This marked the true end of his dark period. The Climber earned critical acclaim, winning the Grand Prize at the 14th Japan Media Arts Festival. For Sakamoto, the series wasn’t just recognition—it was proof that his authenticity resonated with readers

5. Operatic Reach: Innocent → Innocent Rouge and International Acclaim (2013–2020)

From that point on, Sakamoto embraced an unapologetically personal style. His works combined meticulous realism with emotional intensity, exploring themes of freedom, identity, and human fragility.

Innocent (serialized from 2013) and its sequel Innocent Rouge (2015–2020) spun an operatic, baroque saga of the Sanson executioner family before and during the French Revolution—the work that made his name outside manga circles.

His pages began to read as paintings of costume, skin, and fabric; the precision and density of the art became a signature. Innocent Rouge later received an Excellence Award at the 24th Japan Media Arts Festival.

6. Museums, Millions of Eyes, and Today (2016 → present)

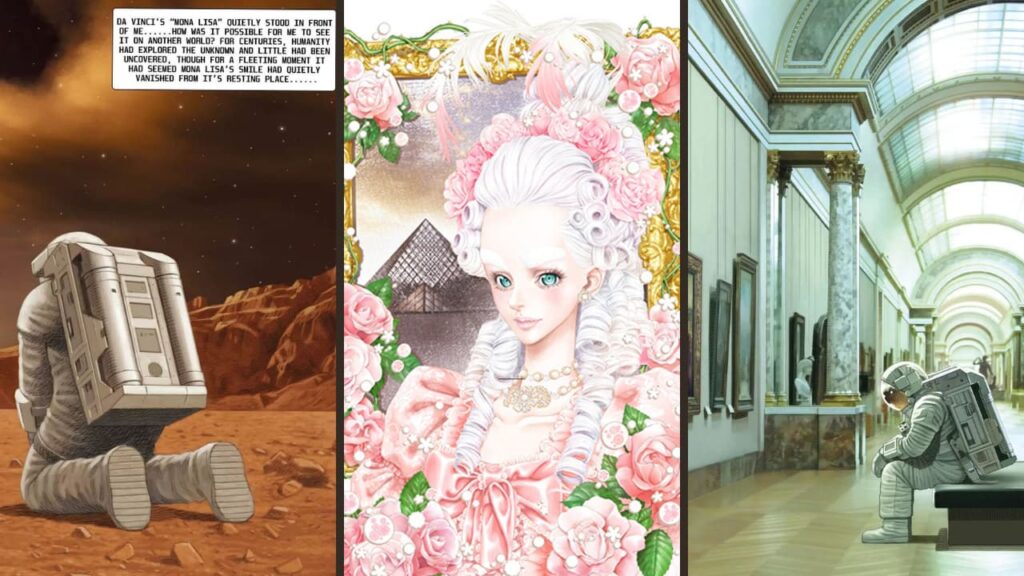

Sakamoto’s paintings have crossed into the art world: in 2016, he participated in the Louvre Museum BD Project / Louvre No.9 exhibitions, a sign that his imagery speaks beyond manga readerships.

His Instagram account (over 200k followers) and international exhibition invites show how recognizable and transportable his visual voice has become; his pages now read as artworks that travel cultural borders.

He continues to push formal limits with #DRCL midnight children (serialized in Grand Jump), a radical, vampiric reimagining of Dracula that extends his cinematic composition into new thematic territory.

Reflecting on his decades-long struggle, Sakamoto notes that even his failures had value:

“It took me a long time to grasp the secret. But because of that time, I learned how tough creating manga really is, and I gained a deep respect for all manga artists. Looking back, I think even those struggles were good for me as a person.”

Sakamoto’s trajectory is not a linear climb from competent to great—it’s a cycle of imitation → collapse → methodical rediscovery → radical expansion.

The artist who once confessed to drawing “borrowed pictures” deliberately rebuilt his practice until his pages became so overloaded with information that they read like paintings.

That stubborn refusal to accept the medium’s limits—combined with a late blooming of personal subject matter—explains why his work now feels both unbearably intimate and monumentally public.

Art Style & Evolution

Sakamoto’s artistic journey is as dynamic as the stories he tells. In his early works of the late 1990s and early 2000s, he relied on traditional pen-and-ink techniques, drawing in a style that leaned heavily on sharp lines and expressive character work. This was the foundation on which he built his reputation—raw, bold, and direct.

As his ambitions grew, so did his methods. By the mid-2000s, Sakamoto embraced digital illustration, long before it became the industry standard.

He began using Cintiq tablets and Clip Studio Paint to layer photographic textures, 3D models, and etching-like effects into his pages. In works like Innocent and Innocent Rouge, this approach gave his panels an almost Renaissance painting quality—ornate, surreal, and strikingly detailed.

But Sakamoto never treats tools as boundaries. In a later interview, he revealed his experimentation with drawing manga on a smartphone (Galaxy Note20 Ultra 5G) using the S Pen. To his surprise, the device felt natural:

“It’s absolutely perfect. My first impression was that it felt great, because I could draw the lines I wanted to draw, or rather, the intention behind them, in a straightforward, flowing way… I thought it might feel strange to run a pen across glass, but it felt so comfortable to write with, and I had a strange feeling that I wanted to keep running with this pen forever.”

Initially skeptical about the small screen, he soon discovered that the compact format even offered advantages, allowing him to see the page from a bird’s-eye perspective. For Sakamoto, whether on a large tablet or a palm-sized phone, what matters is the immediacy of line—capturing intention directly into the image.

This technical evolution mirrors his thematic one: just as his stories shift from schoolyard brutality (Kokou no Hito) to historical grandeur (Innocent) to grotesque metaphor (#DRCL), his art style continually mutates. Sakamoto’s work proves that both human experience and artistic expression are never static—they are always in motion, always searching for new forms.

Best Manga By Shinichi Sakamoto: Core Works, Explained

TL;DR (Quick Picks)

- The One to Start With: The Climber (Kokou no Hito) – Sakamoto’s turning point; a raw, immersive portrait of obsession and solitude.

- The Magnum Opus: Innocent → Innocent Rouge – operatic, hyper‑detailed historical drama about the Sanson executioner dynasty and the birth of revolution.

- The Ongoing Masterclass: #DRCL midnight children – a radical, sensual reimagining of Dracula with Sakamoto’s most cinematic layouts to date.

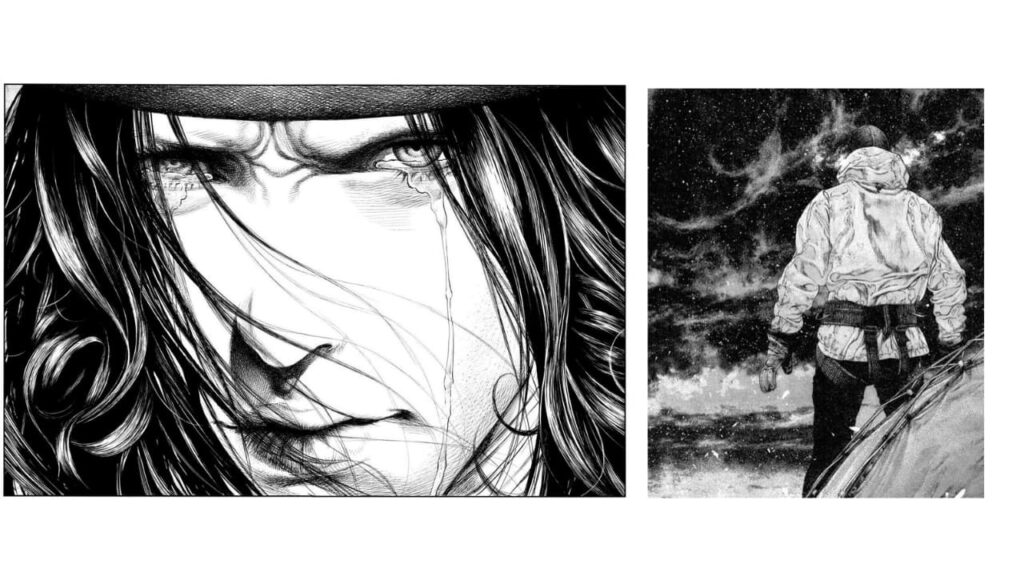

The Climber (Kokou no Hito)

If The Climber marks anything in Shinichi Sakamoto’s career, it’s the moment he abandoned the comfort of formulaic storytelling and embraced the visceral, the symbolic, and the terrifyingly human. Co-authored with Yoshirō Nabeda and based on Jirō Nitta’s novel, the series follows Buntarō Mori, a loner who discovers rock climbing and gradually transforms it into a near-religious pursuit of purity.

At first, the manga reads like a sports drama—high-school dares, muscle tension, walls, and rooftops. But Sakamoto quickly pivots. The higher Mori climbs, the more the story sheds realism for psychological abstraction.

Mountains become bones jutting from the earth, avalanches swallow cities whole, and silence presses on the page like an oppressive fog. His panels mimic hypoxia, dizziness, and the white-out of death. What begins as a boy’s hobby becomes a descent into obsession, self-erasure, and the fragile ecstasy of standing where no human should.

The Climber won the 2010 Japan Media Arts Festival Excellence Prize, but more importantly, it revealed Sakamoto’s defining instinct: to use manga not as a window into reality but as a medium to collapse sensation, metaphor, and psyche into a single visual experience.

Why it matters: It’s the bridge from Sakamoto’s early conventional works to the psychological, symbolic, and suffocatingly visceral style of Innocent and #DRCL.

Themes: Isolation, the beauty and terror of nature, purity of craft, and the thin line between mastery and annihilation.

Best for: Readers of Blue Period or Golden Kamuy who crave something darker, lonelier, and more surreal.

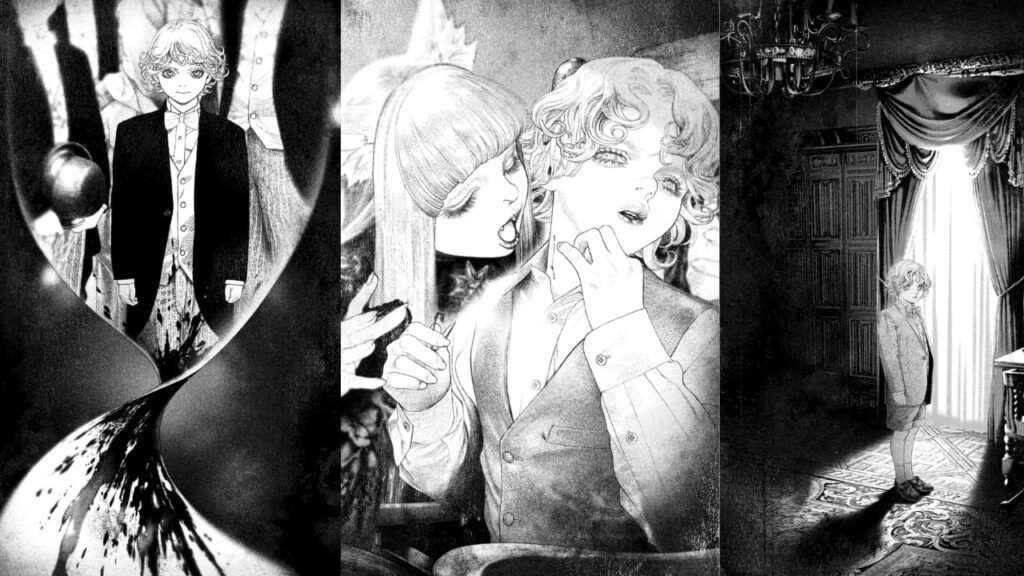

Innocent & Innocent Rouge (2013–2020)

If The Climber was Sakamoto’s leap into psychological intensity, Innocent is where he staged that intensity on the grandest possible stage: the French Revolution. Across Innocent and its sequel Innocent Rouge, Sakamoto chronicles the Sanson family of royal executioners, beginning with Charles-Henri Sanson—the historical figure who oversaw the beheading of Louis XVI—and continuing through his younger sibling Marie-Joseph during the Revolution’s fever pitch.

On paper, this is historical fiction. On the page, it’s something else entirely. Lace, velvet, guillotines, and bodies are rendered with the care of haute couture photography. Scenes unfold less like narrative beats and more like tableaux vivants—bloody, baroque, and strangely beautiful.

Charles is drawn in shadows and black silks, cursed by a profession that makes him despised even as he seeks compassion and reform. Versailles, by contrast, glows white: gowns, chandeliers, powdered wigs. But Sakamoto refuses easy binaries of light and dark—both palace and scaffold are shown as corrupt, cruel, and absurd.

His metaphors reach new heights of spectacle. The mob that executes Louis XVI is visualized as a newborn golem, staggering with uncontrollable power. Antoinette’s fall is depicted through shifts in visual style—at one point, reframed as a shōjo manga, her severed head blossoming into a bouquet. Blood spirals, dances, and flows in impossible arcs. Each execution is not just an act but a stage performance, a moral anatomy lesson, and a meditation on what innocence really means.

The result is a saga that reads like Barry Lyndon spliced with Rose of Versailles, but executed with the psychological ambiguity of Monster. Duty collides with empathy, gender becomes a performance, and history itself is reduced to flesh and spectacle.

Why it matters: Sakamoto’s career-defining work, where his technical precision, symbolic extravagance, and thematic daring hit their apex.

Themes: Innocence as cruelty, justice as theatre, the performance of gender, power and complicity, beauty within brutality.

Signature scenes:

- Charles-Henri’s first execution was staged as both a sacred ritual and a desecration.

- Marie-Joseph’s flamboyant, gender-defiant displays of power.

- The Revolution personified as a monstrous infant, with Jacobins dancing on its back.

- Antoinette’s last gaze refracted through shōjo-style innocence and grotesque beauty.

Best for: Readers who savor prestige political dramas (Rome, The Crown) but want them sharper, stranger, and rendered with operatic draftsmanship.

Edition notes: Innocent is available in English omnibus editions; Rouge is beginning to follow. In 2019, the saga even inspired a stage musical featuring Mika Nakashima—further proof of its grand, theatrical DNA.

#DRCL Midnight Children (2021– )

With #DRCL midnight children, Shinichi Sakamoto completes a kind of trilogy of his artistic vision: after the solitary interior climb (The Climber) and the operatic historical stage (Innocent), he turns to gothic horror. Serialized since 2021 in Grand Jump, #DRCL reimagines Bram Stoker’s Dracula through Sakamoto’s signature blend of visual audacity, symbolic density, and moral ambiguity.

The setup is deceptively familiar: at the end of the 19th century, amid the Industrial Revolution’s upheavals, a mysterious shipwreck off Whitby introduces Dracula’s presence. But instead of the expected cast, Sakamoto recasts the story through a group of schoolchildren—Mina, Luke, Arthur, Joe, Quincy—whose youth and vulnerability transform the tale into something stranger, more uncanny. The gothic becomes couture-horror: blood as fabric, hair as weapon, shadows as stage curtains.

Where Innocent filled every panel with velvet and lace, #DRCL embraces space and silence. Full-bleed spreads breathe like nightmares; typography, smoke, and feral hair spill across the page as if the manga itself were mutating under Dracula’s touch. Horror is not gore alone but dread, intimacy, and transformation. Bodies bend, dissolve, and reassemble in ways that feel both terrifying and exquisite.

For Sakamoto, Dracula is not just a monster but a metaphor for the indiscriminate force that infects and disrupts society—COVID-19 being a recent parallel he cites. His Dracula is an enemy without preference or motive, a contagion of desire and violence that collapses categories of gender, power, and love.

In interviews, Sakamoto has said that #DRCL is his attempt to overturn even his own “common sense”: to question whether romance must always be boy-meets-girl, whether identity must stay fixed, and whether horror itself must obey conventions.

The result is a work that feels both primal and contemporary: Dracula as pandemic allegory, as gendered performance, as cosmic body horror.

Why it matters: Sakamoto brings his lifelong fascination with horror to maturity here, fusing it with the moral and visual daring of his earlier works. It is horror not as a genre exercise but as the completion of his artistic worldview.

Themes: Desire as infection, the body’s truth vs. the social mask, metamorphosis, collective struggle against unseen enemies.

Signature techniques:

- Blood drawn as constellations and fabrics.

- Hair and shadow are used as living panel borders.

- Shifts in style to capture dread—negative space as loud as detail.

Best for: Readers who admire Junji Ito’s unease or the lush gothic of Monstress, but want it filtered through Sakamoto’s couture-horror lens.

Status: Ongoing. It received the inaugural American Manga Award for Best New Manga in 2024, presented by the Japan Society and Anime NYC.

Appendix: Early Works

- Bloody Soldier (1995) – bare‑knuckle action; embryonic experiments with anatomy.

- Mortal Commando Guy (1995) – pulp violence; seeds of kinetic framing.

- Niragi Kioumaru (2004) & Masuraou (2005) – transitional titles edging toward the realism later perfected.

These are fun for archaeology; the canon remains The Climber, Innocent/ Rouge, and #DRCL.

How Sakamoto Draws — Mini-Craft Primer

Shinichi Sakamoto’s process is a collision of obsessive craft and practical adaptation. He’s a creator who cares about the intention behind each stroke, but who also embraces whatever tool or trick lets him realize that intention — from brush pens to Cintiqs to a Galaxy Note in his hand. Below are the core elements of how he works, drawn directly from his interviews.

1) Why and when he went digital

Sakamoto switched to digital around the end of Kokō no Hito and the start of Innocent — roughly five years before he spoke about it. The reason was simple and technical: with analog tools, he “could no longer draw the lines I wanted.” He needed a toolset that could hold the exact line quality and allow him to experiment without the anxiety of permanent mistakes.

“With digital I can go back, so I can freely try out any technique that comes to mind… I get more and more particular about it, which ends up taking longer, but there’s a joy in being able to pursue expression to the fullest.”

Still, he admits the learning never stops: even now, he feels he needs to study more and relies on staff for much of his digital know-how.

2) Tools & devices: from Cintiqs to smartphones

Sakamoto uses a mixed toolkit: large LCD pen tablets (Cintiq), Clip Studio Paint EX on PC, and — surprisingly to some fans — smartphones (Galaxy Note20 Ultra 5G) with an S Pen.

He praises the Note’s pressure sensitivity and says drawing on glass “felt so comfortable… I wanted to keep running with this pen forever.” He even finds advantages to the small format: the bird’s-eye view and instant capture make it easy to lock down an idea anywhere.

“The best thing about drawing on a smartphone is that you can draw wherever you are… the barrier to entry is very low. I like the speed at which I can instantly capture the image I have in mind.”

3) Storyboarding: scenes first, plot later

Sakamoto begins by prioritizing scenes he wants to draw. He develops storyboards at his desk, but also lets ideas gestate while walking or drinking tea. He often finds his most urgent storyboard ideas under pressure (frequently on Tuesday evenings).

“I prioritize the scenes I want to draw and the feelings I want to express… I assemble and weave a story in order to convey the scenes I want to depict.”

This approach makes his manga scene-driven rather than plot-driven: the narrative is constructed to serve the images that carry emotional weight.

4) Photographic staging and staff collaboration

Sakamoto’s studio approach is theatrical. He stages live photo shoots with staff in costumes to capture authentic poses, fabric behavior, and tiny details (wrinkles, cape motion, etc.). Costumes are sourced — sometimes from Harajuku visual-kei shops — and reused as references.

Photos are not pasted directly; they are embedded, cut, warped, and transformed on the canvas. He deliberately exaggerates proportions for visual vitality (often aiming for figures ~11–12 heads tall). Backgrounds mix his Paris photographs and period paintings to rebuild 18th-century cityscapes.

5) Line philosophy: intention over literal lines

Sakamoto is skeptical of “lines” as absolute. He argues that features like noses and hands are really boundaries formed by light and shadow rather than strict outlines. In practice, he often draws lines and then erases them to avoid overly rigid edges — and says he would someday like to draw a manga with “no black lines at all.”

This is why his linework reads so sculptural: it’s not just contouring, it’s modeling light.

6) Toning and finishing: hand warmth in a digital age

Although he uses digital tools, Sakamoto avoids canned halftone shortcuts. He prefers to paint in grayscale and then convert those grays into halftone tones (Clip Studio has tools to help), layering overlapping lines and touches to retain a hand-made warmth. For heavy decorative work (lace, embroidery, furniture), he delegates to specialist staff and asks them to “let go and enjoy the manuscript”—a call for expressive, not mechanical, finishing.

7) Character design: quick recognition and psychological hinting

He believes readers must quickly “befriend” characters, so visual shorthand is crucial. Details like thick eyebrows on Antoinette are deliberate choices meant to communicate background and psychology fast: “Thick eyebrows are a symbol of the natural, unrefined sleaze of a young girl” — a small feature that carries a lot of implied personality.

8) Emotional engine: obsession, dissatisfaction, and bursts of urgency

Sakamoto is brutally honest about his relationship to finished work: he often feels intense dissatisfaction and pain when reviewing manuscripts — and then refocuses for the next 28 pages.

But when a scene hits him fully, he draws it with reckless urgency: “My heart beats fast and I want to publish it as soon as possible, and I would even be willing to die if I could draw it.” That emotional rhythm — despair at the imperfect and ecstasy when the image arrives — powers his best pages.

9) Workflow summary (step-by-step)

- Storyboard & seed idea (often low-pressure, walking/tea).

- Photoshoots with staff in costume; reference gathering (photos, paintings).

- Embed photo references, warp/transform for composition.

- Rough sketches and roughs based on photos and vision.

- Linework with attention to the intention of the line (erase, rework).

- Grayscale painting, layered hand-like infill, convert to halftones as needed.

- Staff finishing for backgrounds, decorative detail, and toning.

- Final review (personal dissatisfaction + revision loop).

Takeaway — what makes Sakamoto’s craft unique

- He prioritizes intention over technique: tools are chosen to capture what he wants to express.

- He blends theatrical, photographic staging with painterly linework and digital flexibility.

- He treats staff not as assistants to speed production but as specialized collaborators who contribute artistry.

- He pursues an aesthetic of modeled light rather than hard outlines — even dreaming of a line-free manga.

Final Recommendation

Shinichi Sakamoto isn’t merely a great manga artist; he’s a living proof that a medium can expand its own rules. From the raw, hypoxic pages of The Climber, through the operatic cruelty of Innocent / Rouge, to the mutating dread of #DRCL, his work traces a single obsession: to force image, emotion, and meaning into one uncompromising visual event.

He remade his tools to match his intent (brush pens → Cintiqs → even a Galaxy Note), rebuilt his storytelling around scenes that demand to be seen, and taught a studio to treat reference and collaboration as artistic extension rather than labor-saving trick.

What remains striking is the paradox at the heart of his practice: Sakamoto’s pages feel both hyper-designed and unbearably human. He chases perfection and then distrusts it; he embraces new tech while preserving hand-warmed texture; he stages grand metaphors and yet never lets them outrun the person standing at the center of the frame.

That tension—between mastery and vulnerability, spectacle and intimacy—is why his work keeps drawing readers back and why it will matter to manga history.

If you want one manga to decide whether Sakamoto’s for you, start with Innocent Omnibus Vol. 1. If it grabs you (it will), queue The Climber next to see where this visual language was forged, then ride directly into Innocent Rouge and #DRCL. Few creators invite rereading as urgently—and reward it as richly—as Shinichi Sakamoto.